Can animals reason without language? Transitive inference (TI) is the ability to deduce indirect relationships—for example, understanding that Mary is taller than Kate if you know Mary is taller than Ann and Ann is taller than Kate.

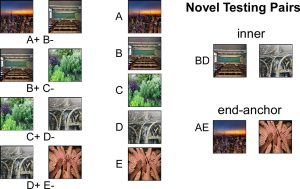

In nonverbal TI tasks, animals are trained on a sequence of overlapping pairs:

A+ B−, B+ C−, C+ D−, D+ E−

(Where “+” means reinforcement and “−” means no reinforcement.)

During testing, the critical pair B vs. D is presented. Both were sometimes reinforced and sometimes not. Choosing B over D is taken as evidence of TI: If B > C and C > D, then B > D.

What We Found

Across several studies, we’ve shown that behavior in this task can’t be fully explained by reinforcement-based models (e.g., Lazareva & Wasserman, 2006, 2010; Paxton Gazes et al., 2014; Lazareva et al., 2020).

In fact, we found that hippocampal lesions impair TI-like behavior only in pigeons who aren’t relying on reinforcement values during test. Those that are using associative strategies remain unaffected (Kandray, Acerbo, & Lazareva, 2015). This suggests that animals—even within the same species—may rely on multiple strategies when solving these tasks.

Our recent work in collaboration with Hampton’s lab(Paxton Gazes et al., 2014) suggests that animals may use a spatial representation of item order in transitive inference tasks. Instead of relying solely on associative strength, they may mentally arrange items along a line, with closer items more easily confused. This spatial model offers a compelling alternative to associative accounts and brings animal performance closer to how humans solve similar tasks.

Recent Developments

Transitivity is a task that seems to be conceptually related to transitive inference; however, the two tasks have not been compared directly. Our recent publication in The Conversation explains why this comparison is necessary, and our lab is currently working on collecting data addressing this question.